More about the Ring-Story

The odyssey began in April 1945, when Holmquist and three other American airmen aboard a B-24 died in a crash near Plaus, a town north of Florence. A ring was recovered from the crash site, but no one knew to whom it belonged.

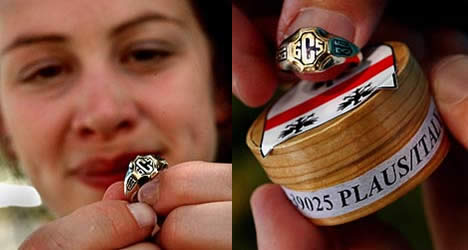

The ring bears the date 1936, and the initials "D.L.D" are inscribed inside the band -- details that helped those trying to determine its owner to narrow the search to Holmquist.

His wife's maiden name was Dorothy L. Dysle.

Alexander said the ring likely was her grandmother's baseball team ring when she played on a high school girls' squad in Camino.

The ring was cut to fit Holmquist's finger, and he likely wore it as a good-luck charm during the war, Alexander said.

The ring is being held by a Plaus historian as part of a "memory case" dedicated to the four dead American airmen, Alexander said.

But the effort to return the ring to its owner's family has been an ongoing international effort since at least 1990.

That's when Iris Knight, a World War II history buff who lives in Great Britain, said she began her quest to solve the mystery. Her only clue was the initials "D.L.D."

In an e-mail to Neighbors, Knight said she was motivated by a desire during her years collecting books about World War II to say "thank-you" to American veterans.

"I learned how the war affected not only them but their families, too. And I learned how the children of those killed during the war had grown up without knowing much about their fathers," she said.

A search of military personnel records revealed which of the four airmen was wearing the ring at the time of the crash.

According to Knight, Holmquist was 28 years old when he died. The other three airmen were only 20 -- all unmarried, too young to have had a sweetheart who had graduated in 1936 and with no close relative with the initials "D.L.D."

From there, the hunt was on for Holmquist's relatives. Military records indicated that Holmquist had lived in Placerville and the couple had a daughter, Linda Lee, born in 1944.

"We had a name and a state in which to start searching for your mother," Knight wrote to Alexander about the search, which involved history buffs in Germany, Austria, Italy and the United States.

Locally, users of a Sacramento County resource page at Rootsweb.com, a genealogy Web site used by El Dorado and Sacramento County residents, also were active in the quest for Holmquist's daughter.

Dorothy Holmquist, the searchers discovered, had remarried in 1949, moved to Sacramento and died in 1982. But her daughter Linda, they felt sure, was alive.

As it turns out, Alexander had begun her own search two years ago for information about her grandfather's death. She and her husband, Jason, were planning a trip to Europe. Holmquist is buried in an American cemetery in Florence.

"I was looking for information (on the Internet) for quite a while, but I was coming to dead ends until a couple of months ago," Alexander said.

She learned that one of her aunts had received an e-mail from a man named Helmut in Germany. Helmut had discovered Holmquist's relatives while helping someone research their family tree.

Alexander said it was "totally by accident" that Helmut made the connection.

Jason Alexander remembers his wife's reaction when she received Helmet's e-mail. "Her face just lit up," he said.

Linda said the news was "like hearing from somebody in the past."

But that wasn't all. Shortly afterward, Alexander contacted an American historian who specialized in World War II bomber groups. He said he knew of a photograph of her grandfather in a book titled "Force for Freedom."

When Alexander received an e-mail photo of her grandfather in uniform, it was the only photograph of him that she had ever seen.

That and another group photo in the book are the only photos Alexander and her mother have of Holmquist.

"When (Alexander) said she had a picture of him, it was like 'Oh, my God,' " Linda recalled.

Alexander said she still receives e-mail messages from people in Austria, Germany, Great Britain and Italy, saying, "You don't know me but . . .' "

Although Alexander said she would like to have the ring, those holding it in Italy are afraid it could get lost in the mail. And although there's a possibility the U.S. Air Force could deliver the ring, Alexander said she and her husband likely will pick it up when they travel to Europe in June.

Linda said she won't accompany them because of her fear of flying.

"I told (Crystal) to put some flowers on my father's grave," Linda said.

In a recent message to Alexander, Knight said, "Although I have worked on many things concerning WWII and the consequences . . . as a mother and grandmother, this search has touched me far more deeply than any other I have undertaken during the past 12 years or so. Many tears have been shed as I searched the records.

"Men like your grandfather gave their lives for our freedom. We owe them far more than we can ever hope to repay."

WWII flier's ring finally home:

For nearly 60 years, the villagers of Plaus, Italy, sought to return a simple ring to the family of an American soldier killed while liberating their region from German control.

Their wishes were fulfilled a week ago when the ring -- taken from the ashes of a World War II crash site -- was presented to the man's family in Orangevale.

Now that ring is in the hands of Linda Holmquist Darrach, whose father, Sgt. Harold D. Holmquist of Placerville, died in the 1945 crash. For history buffs in the United States and Europe, it is a mystery solved. For Holmquist's family, it is reason for joy.

"Isn't it amazing?" Darrach said during a family gathering at her son Scott's home. "I'm grateful to the people of Plaus, especially for what they did at the time of the crash."

Not only did the townspeople preserve the ring in a small shrine, their mayor was able to prevent Holmquistand the three B-24 fliers who died with him from being buried in a mass grave by the German army.

The ring was retrieved this spring by Holmquist's cousin Walt Wegner -- a former Army Air Corps navigator who had trained at the same base as Holmquist in 1944.

Until last year, Holmquist's surviving family knew little about what had happened to him in the war.

"As long as I live and breathe, I'll search for more information about my dad," said Darrach, a baby when her father was killed.

Now she and her family have stories and information gathered by dozens of strangers and friends such as Iris Knight. A World War II history buff who lives in the United Kingdom, Knight was instrumental in tracking down the story behind the ring.

On April 8, 1945, one month before the war in Europe would end, Holmquist and the 10 other crew members of his B-24 were fired upon by the German army while flying a bombing mission over northern Italy. Their target was a railroad bridge in the town of Vipiteno -- part of an Allied effort to destroy enemy transportation systems.

"They had been hit rather badly. Two engines on the left side were shot out," said Knight, who corresponded with people in Germany, Austria, Italy and the United States.

"The ship was rocked by three rapid explosions," bombardier Sheldon Benscoter told Knight last summer in a recorded interview. "I could hear the sound of flak hitting the ship. When we were hit, I glanced out of the left blister and saw the propellers on the two engines on the left wing were just windmilling and fuel was streaming out of the left wing."

With the aircraft losing altitude at a rate of 1,500 feet per minute, the pilot ordered the crew to bail out. Holmquist, the radio operator, apparently died before he reached the ground.

The aircraft crashed into a hillside less than a mile from Plaus, a German-speaking Italian village of about 500 people.

Wegner said the Germans captured seven of the crewmen and imprisoned them in a makeshift jail. They eventually were taken to a POW camp in Munich.

Although the Germans wanted to bury the four dead American soldiers in a mass grave, the mayor intervened and paid for coffins out of his own pocket. Holmquist and two members of his crew were buried at an American cemetery in Florence. The fourth soldier's remains were returned to the United States.

A small ring was recovered at the crash site, but no one knew to whom it belonged. It bears the date 1936 and is inscribed "D.L.D." inside the band. Those details later helped narrow the search for the owner to Holmquist, whose wife's maiden name was Dorothy L. Dysle.

Crystal Alexander, Holmquist's granddaughter, said the silver-and-blue ring was probably her grandmother's Girl Scout ring, from when she lived in Camino. It was cut to fit Holmquist's finger, Alexander said.

Since 1945, the ring had been kept by Plaus town historians in a "memory case." The effort to return it to its owner's family picked up steam about 13 years ago, after Knight learned from a German man of the town's interest in solving the mystery.

Knight, who was a child during the war, said she was motivated to thank American veterans for their role in the war -- and by the children who had grown up without knowing about their veteran fathers.

Using military records, Knight concluded that Holmquist was the likely ring owner. He was the only one of the dead men who was old enough to have had a sweetheart who had graduated in 1936. None of the others had a close relative with the initials "D.L.D."

War records disclosed that Holmquist had lived in Placerville. Knight and others who joined the search had a name and a state with which to work.

Dorothy Holmquist, the searchers discovered, had remarried in 1949, moved to Sacramento and died in 1982. They decided to search for her daughter, Linda, who was born in 1944.

Coincidently, Alexander had begun her own search three years ago for information about her grandfather's death. She ran into dead ends until an aunt gave her the contact information for a man in Germany helping someone else research a family tree. It was the same man who had told Knight of the ring in Plaus.

From there the pieces began falling in place.

Knight and others contacted Alexander through the Internet. A trip Alexander planned to Plaus last year to bring back the ring fell through, but Wegner and his wife, Maxine, Southern California residents, were taking a monthlong visit to Europe in April.

When the Wegners arrived in Plaus, about 20 miles from the Swiss border, they were taken to the crash site, now surrounded by apple orchards. A memorial plaque, erected two years ago, bears a solemn message in German: "In sorrow, in death and in mourning, all men are the same."

At one ceremony, two trumpeters dressed in Tyrolean costumes played "My Comrade." At a second ceremony at City Hall, the Wegners were presented the ring. They then traveled to Florence to visit Holmquist's grave.

Wegner told the people of Plaus: "There is a poem that says 'God only takes the best,' and Harold was one of the best."

During an informal ceremony last weekend, Walt Wegner fought back tears as he handed Linda Holmquist Darrach a modest wooden box containing her mother's ring, which her father took to his death.

"With pride and great humility, I present this ring," Wegner said. "It took 58 years to make the trip from Plaus to here."

Thanks to Walter Yost for writinge this article.